Storing Things in Code - Variables

So far, our code has used concrete, static data to create visuals. This kind of data can also be called hard-coded. However, we can use updatable, changing data in order to modify our projects while they are running in order to make them more dynamic. To do this, we use variables. A variable is a virtual container that stores a single value in the memory or our code so that we can use it at a later time, in multiple places throughout our code. This make variables more flexible than fixed, hard-coded values.

Take a look at the embedded code below:

See the Pen Example Code by LSU DDEM ( @lsuddem) on CodePen.

https://codepen.io/lsuddem/pen/wXdQOEIn this code, we’ve drawn two polygons to the screen. The teal square is built using four hard-coded values as arguments; its location, width, and height will never be changed unless we stop the code, edit the values, and rerun the program. The pink rectangle uses two variables: “rectWidth” and “rectHeight”. The teal rectangle will always load with the same hard-coded values, however as we will see later, the pink triangle will be able to adapt and change as the code runs. But first lets make a few variables.

Making Variables

To make a variable, we start by declaring a name for the container. In our code, we’ve declared both “rectWidth” and “rectHeight” at the very top of our code by first typing the keyword let. This is synonymous to asking our code to save “rectWidth” contain a specific value in its memory, so that we can refer to it by that name in our project from now on. We’ve done this outside of either the setup( ) or draw( ) functions, which means that we’ve declared these variables globally and they can be used/accessed anywhere in our code (we’ll discuss this in detail at the bottom of the page).

Next, we need to assign an initial value to each variable. This is also called initialization, or init for short. This step can be done immediately after declaring a variable:

let rectHeight = 50;

or at a later time in a function block:

function setup() {

rectHeight = 50;

}

- You can only declare a variable once. If you try to declare it more than once, your code will wipe the previous value inside of your variable from its memory. For instance, the following code is an issue:

let xValue = 1;

function setup() {

let xValue = 21;

}

Because the original value of “xValue”, which was 1, has now be replaced with 21. This new value is also locally trapped inside of the setup function (more on global scope at the bottom of this page.)

- You should not have two separate variables that share the same name. The same code example above would also cause an issue due to the fact that you are attempting to declare two separate variables that share the same name. While this sort of thing is POSSIBLE to do, it makes for a very confusing code for both the computer and the coder.

- When naming your variables you should choose a name that describes how the variable will be used in your code. If you were to look at an example of code and see this:

let x14, hasiyuergthiww, bob, sally, i1l0, variable6;

You would have no idea how any of these variables would be used. This makes fixing errors in the code unnecessarily complicated. The example below is a much better list of names for variables.

- If you are declaring a number of variables without immediately initializing them, you can save some vertical space in your code editor by declaring them all on the same line while using a single let keyword. The example below declares four different variables all on one line, separated by commas:

let circleX, circleY, speed, jumpHeight;

Fixed Values vs. Changeable Values

Variables can contain fixed values as well as changeable values. In our example, rectHeight contains a fixed value of 50 inside of it (which happens at the very top of our code, above the setup( ) function block), allowing us to use the value of 50 in any location we type the phrase “rectHeight.” rectWidth, however, contains the result of a function called random(), which generates a random number between its two arguments each time it is run. Since it only runs inside of the setup( ) block, we need to hit the rerun button in the embedded Result panel in order to get a different width for the pink rectangle. We can easily modify our code so that random() spits out a new value and updates our variable with every frame of the draw loop:

See the Pen Example Code by LSU DDEM ( @lsuddem) on CodePen.

https://codepen.io/lsuddem/pen/BVRVYLNotice that we are referring to the name of the variable, and then using whatever value is stored inside it. (in this case the result of random(1, 400)). We can see that the value inside of the varible is being repeatedly changed since we are using that value to set the width of the pink rectangle.

System Variables

The p5.js library includes a series of built in variables that allow you to monitor the status of certain aspects of your device and use them as ways to interact with your projects. These variables are known as System Variables.

Take a look at the embedded code below to see an example of some common System Variables in p5.js:

See the Pen Example Code by LSU DDEM ( @lsuddem) on CodePen.

https://codepen.io/lsuddem/pen/OEmaYwSince every variable in this example is a System Variable, we cannot declare or initialize them in our code like we would with custom-built variables. Their declaration occurs inside of the larger p5.js library, and their initialization/updating occurs differently based on the variable. width and height are variables that hold the current size dimensions for the project’s canvas and are initialized when the createCanvas() function is called. Open this code on CodePen or copy it into your P5 Web Editor, then change the argument inside of createCanvas() to see how updating those values also updates these variables.

The values inside of mouseX and mouseY are updated every time you move your mouse cursor across the canvas. Using these variables, you can update the location of an object (like we’re doing to one corner of the triangle) or use their current values in a calculation to generate changeable arguments.

Common System Variables in p5.js

Here are some commonly used System Variables found in the p5.js JavaScript library. Remember - we can read these variables, but we cannot reassign them:

| Variable | Use |

|---|---|

mouseX |

current location of mouse on the canvas’ X axis |

mouseY |

current location of mouse on the canvas’ Y axis |

pmouseX |

previous location of mouse on the canvas’ X axis |

pmouseY |

previous location of mouse on the canvas’ Y axis |

key |

current special key pressed (ENTER, UP_ARROW, etc.) |

keyCode |

current key pressed (ASCII keys only) |

width |

current width of the canvas in pixels |

height |

current height of the canvas in pixels |

Boolean System Variables

Boolean variables can only contain one of two values, true or false.

| Variable | Use |

|---|---|

mouseIsPressed |

boolean - contains “true” if mouse pressed, “false” if not |

keyIsPressed |

boolean - contains “true” if any key pressed, “false” if not |

Global Scope vs. Local Scope

Depending on our project, we may need the data inside of a variable to be accessible across our entire code so that we can use/read/change it in every function. In some cases, however, we may only need a variable to exist within a specific function or section of our code. This determination of how widely or narrowly accessible data is available throughout our code is known as scope.

In all of our examples so far, we’ve been declaring our variables outside of any of our function blocks (the ones we’ve used most often are draw( ) and setup( )), mainly at the very top of our code. This process is known as global declaration, and these variables can be used/read/changed anywhere and everywhere in our code. In the example below, the variable “circSize” is declared with the keyword let outside of any function block or function argument, which allows us to initialize it in the setup( ) block, change it in the draw( ) block, and then print it to the console on every click in the mousePressed( ) block.

See the Pen Example Code by LSU DDEM ( @lsuddem) on CodePen.

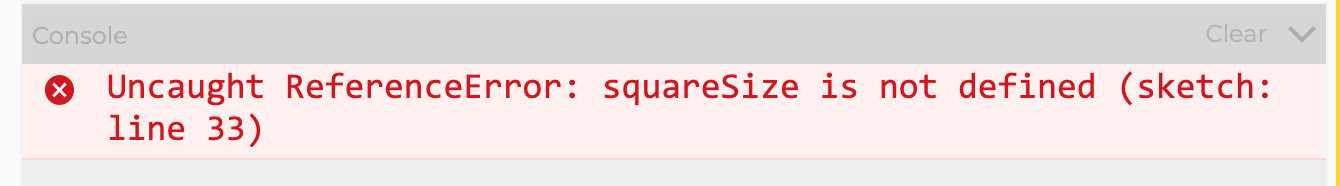

https://codepen.io/lsuddem/pen/joxoqeWe also have a second variable, squareSize, that is declared inside of the brackets of the mousePressed() function. This is known as local declaration. Because of this, “squareSize” can only be used and modified inside of this function. To demonstrate this, copy the entire code from the embedded editor above and paste it into a new sketch on the p5.js Web Editor page. Uncomment the code on line 33, rerun the sketch, and watch for an error in the console. You should see the following text:

This is a common error related to using variables in a project, and in this instance, it is caused because we are trying to read the value of “squareSize” form inside the draw( ) function block. Our code then tells us that it doesn’t understand what “squareSize” is because it hasn’t been properly defined, even though we declared and initialized it. This variable’s local scope won’t allow us to do anything with it outside of mousePressed( ). Try cutting line 33 and pasting it into mousePressed( ) on any line after we declare it, and both console.log() functions will now work properly. You may also get this error if you misspell a variable name in your code. Remember that a computer will read squareSize and squareSize as two entirely different items.

There are a number of reasons why you would want to declare a variable locally instead of globally, but many of them depend on specific circumstances. As we progress through this unit and others, we’ll call attention to instances where we choose local vs. global and explain why this choice is sometimes necessary.

LETS PRACTICE!

Now that we have gone through all of the basic information about variables, you can expect to see them constantly in the sketches for this class. The ability to save and recall data is powerful when working with computer code.

Before moving on, lets try a little practice using variables:

Create a new p5 sketch and use the information from this chapter to draw one of each of these shapes using a custom variable:

- square

- circle

- line

- triangle

Be sure to both declare and initialize the variables before you use them, and try to make them all global variables.

Then, create an additional ellipse(). Experiment and see what happens when you use the system variables mentioned in this lesson co control the different arguments. (mouseX and mouseY can be extremely useful) Try and achieve different results by using different system variables in different places inside the ellipse() function.